How leading design firms are revolutionizing their workflows

Streamed live in January 2022, aec+tech hosted its first event of an AEC-tech talk series focused on emerging design technology practices in the AEC/O discourse. The event brought in three speakers from reputed Architecture and Engineering firms — Buro Happold, Henning Larsen, and Stantec, to share their insights on what computational design trends and developments have taken place in their respective offices.

Michael Hoehn — Buro Happold

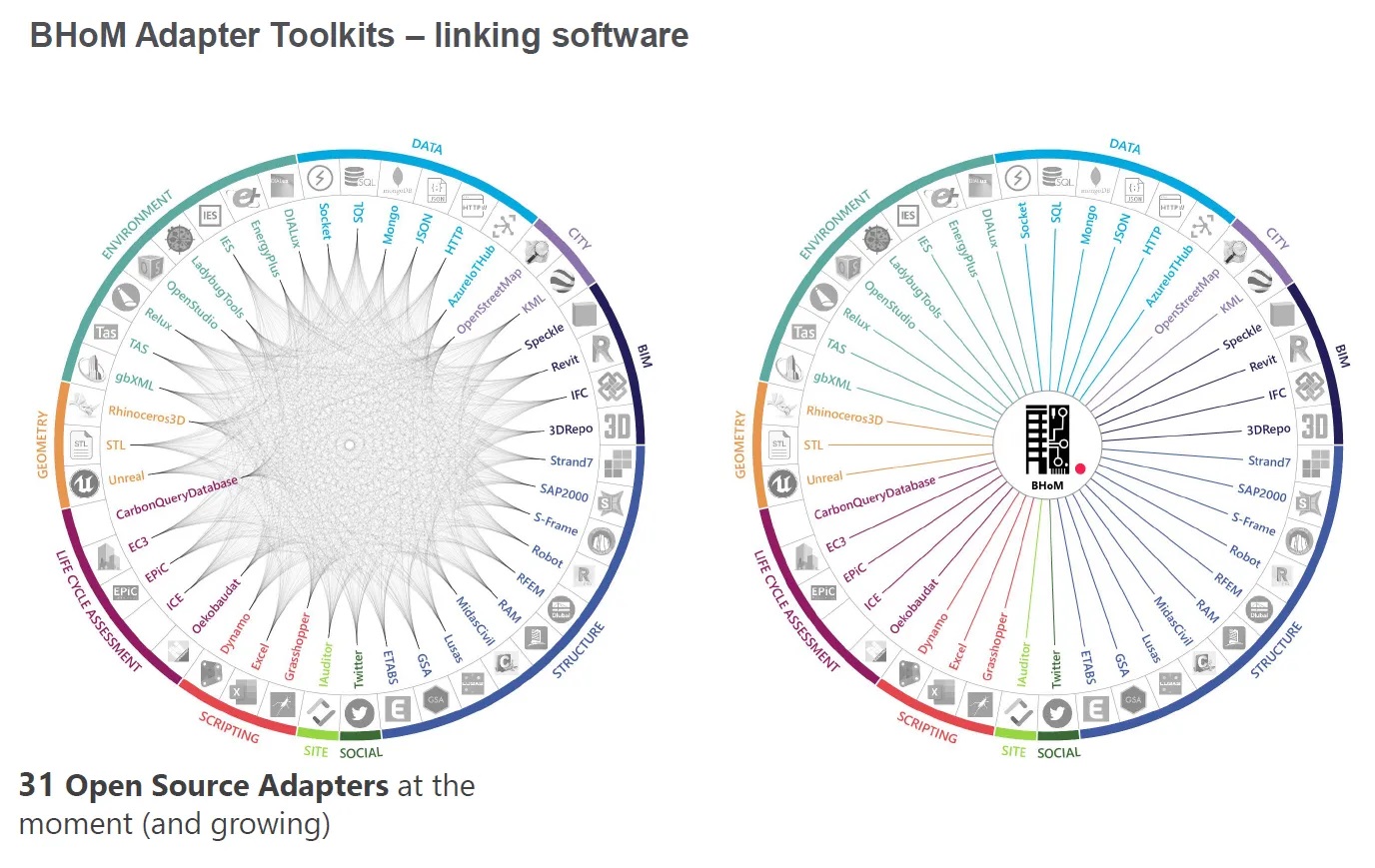

Michael is a senior computational designer with Buro Happold where he helps a variety of teams solve complex problems through planning and executing computational workflows. Michael has recently led initiatives throughout the US and UK offices in developing digital tools for evaluating embodied carbon within the company’s open-source coding platform called Buildings and Habitats Object Model BHoM which won the 2020 AIA technology in architectural practice innovation award.

According to Michael, BHoM is an object-oriented and flow-based programming framework that helps tackle the immense level of complexity that is very often prevalent in architectural projects.

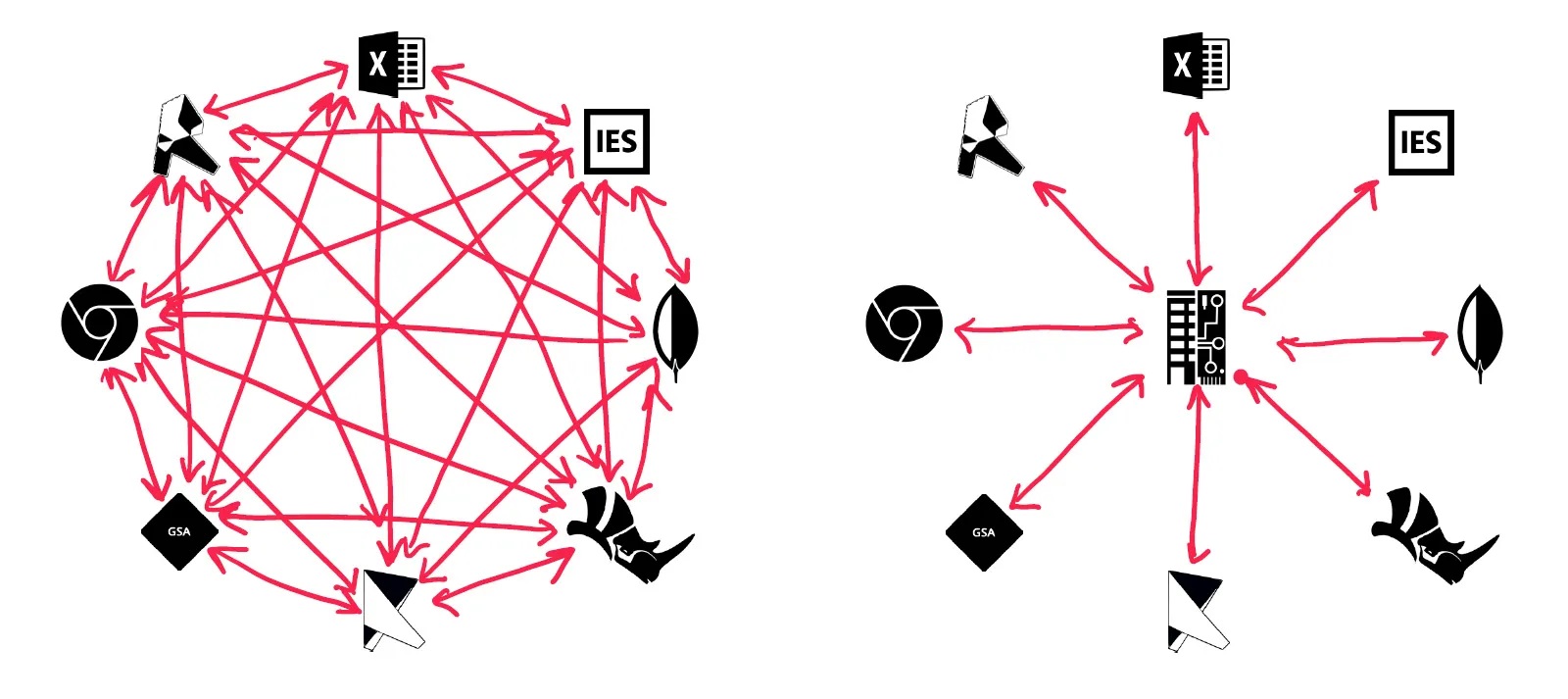

This complexity arises across multiple levels, all the way from the structural schema, the envelope, the architectural programming, people flow, and so on. It is likewise reflected in the models that are created for design and analysis. Thus presenting a need for the ability to manipulate and control the different layers of models and elements created, in a way of making them accessible through a large set of applications and thus use cases. BHoM evolved as an interoperability software connecting everything to everything, everything to everyone, and everyone to everyone, progressively reflecting natural ways of working in design practices.

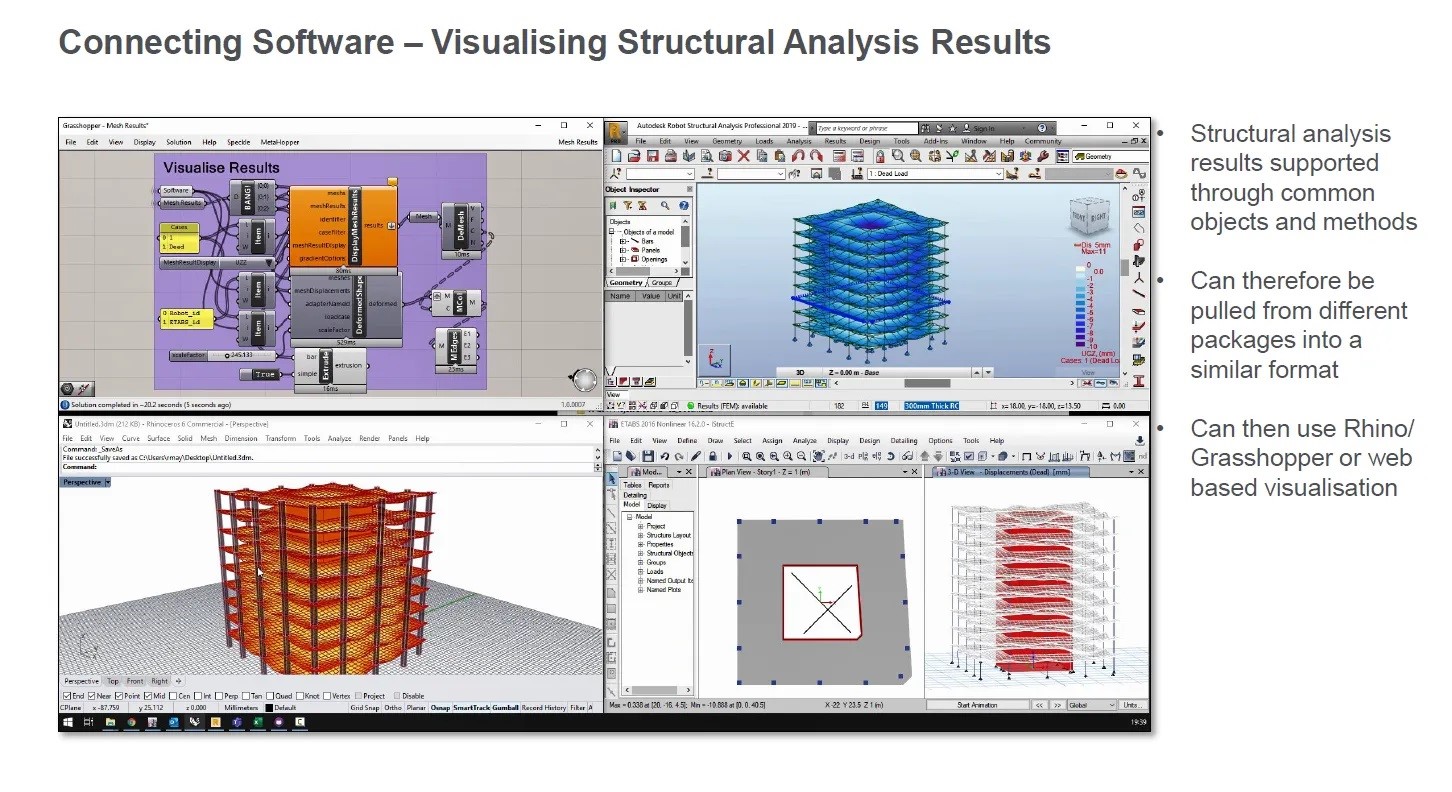

Distinct elements delineate the interoperability in the BHoM framework: adapters link to and from other pieces of software — Rhino to Revit being the most popular one in the industry. To impart the adapted geometry information that could be widely distributed to all the stakeholders in the design and construction process, a set of properties are defined for the objects in the ecosystem — both high level and low level — such as material density, embodied carbon footprint, etc — which could be accessed and utilized by anyone in the production loop. This enables highly efficient and rapid information transfer across multiple stages of architectural creation. BHoM hence wraps all of this into a single toolkit, drastically reducing the time and complexity through conventional processes.

In addition, BHoM is designed in a way that a single download provides access to the tool inside all other design software and toolkits. The more information transferred to the objects created, in any design software, the smarter the object becomes. The flow-based programming framework is essentially a way of looking at these elements agnostically, providing a very high degree of organization and interaction amongst design models. The BHoM engine then allows for users to work with the objects, modify, query, run calculations on them concurrently being inter-operable.

BHoM enables designers to push and pull a model and devise their own custom workflow: you could use multiple different programs running side-by-side, all acting in sync with one another. You can run a full-fledged structural analysis in Rhino and Grasshopper, push it into Revit or Robot, and complete tasks in a highly methodical and orderly fashion.

Mikkel Steenberg — Henning Larsen

Mikkel Steenberg is the Lead of Henning Larsen’s computational design team and is responsible for digital workflows. Mikkel has been involved in the development of several simulation programs, used primarily for early-stage development and combining architecture and engineering from the very beginning of each project.

Mikkel says that Generative Design is a way of making the computer explore various design options/variants, solving for a set of given, pre-defined constraints.

It is made stronger when combined with the idea of Augmented Design, where a live analysis runs alongside, identifying critical goals/parameters for development/modification. This framework makes possible immediate feedback on each design alternative generated, evaluating the designs on the go. It lets the user know what attributes to focus on, what should be avoided, and offers cues for approaching crucial conditions. Besides generating design configurations for a set of constraints, the augmentation component renders a deep understanding of the project’s potential and offers a way forward to achieving them in the process of design creation.

The idea of Augmented Design, he says, is very close to Iron Man’s Jarvis, providing the right kind of information to designers at the right time. This comes as a long way of enabling non-tech-savvy designers to be able to harness the ability of computation to its fullest.

This technology has widely been implemented in multiple of Henning Larsen’s projects, from the scale of a façade, to overall masterplans. Mikkel states that their team rarely optimizes design goals to produce a single output, due to the high diversity of parameters governing the output. As a result, they use it to explore the design space throughout, letting the designers open up their minds on what kind of options to go for. In certain cases, there are times where the parameters used to create an output are contradictory; for example, solar irradiance vs. daylighting in a tropical setting, here the generative and augmented design framework try to strike a balance between the two. Ultimately, there’s no one right way to use Generative Design in a workflow; its potentials are vast and expanding.

Generative Design goes a step ahead to be used as a co-creation tool as well. Mikkel talks about a project, whose highly stringent bylaws prevented design exploration considerably. Usage of this framework has enabled the designers to come up with unexpected solutions. Within a series of meetings, the clients ended up experimenting on the potentials of the site through this framework, participating in the design process, and introducing a different level of engagement. The project saw as many as 5000+ variants created in a short span of time to be assessed for feedback and further evolution; this was translated into the form of a database where one can search for designs prioritizing on specific goals, narrowing the window for evaluation. A single output was chosen after analyses, to be later developed further.

Mikkel reinforces the idea that although it is clearly identifiable as to where the output came from, it was always designed thereafter to become an architectural product.

Alireza Memarian — Stantec

Alireza Memarian is an Architectural designer in Stantec, Boston, with 10 years of experience in computational design and developing tools for architects.

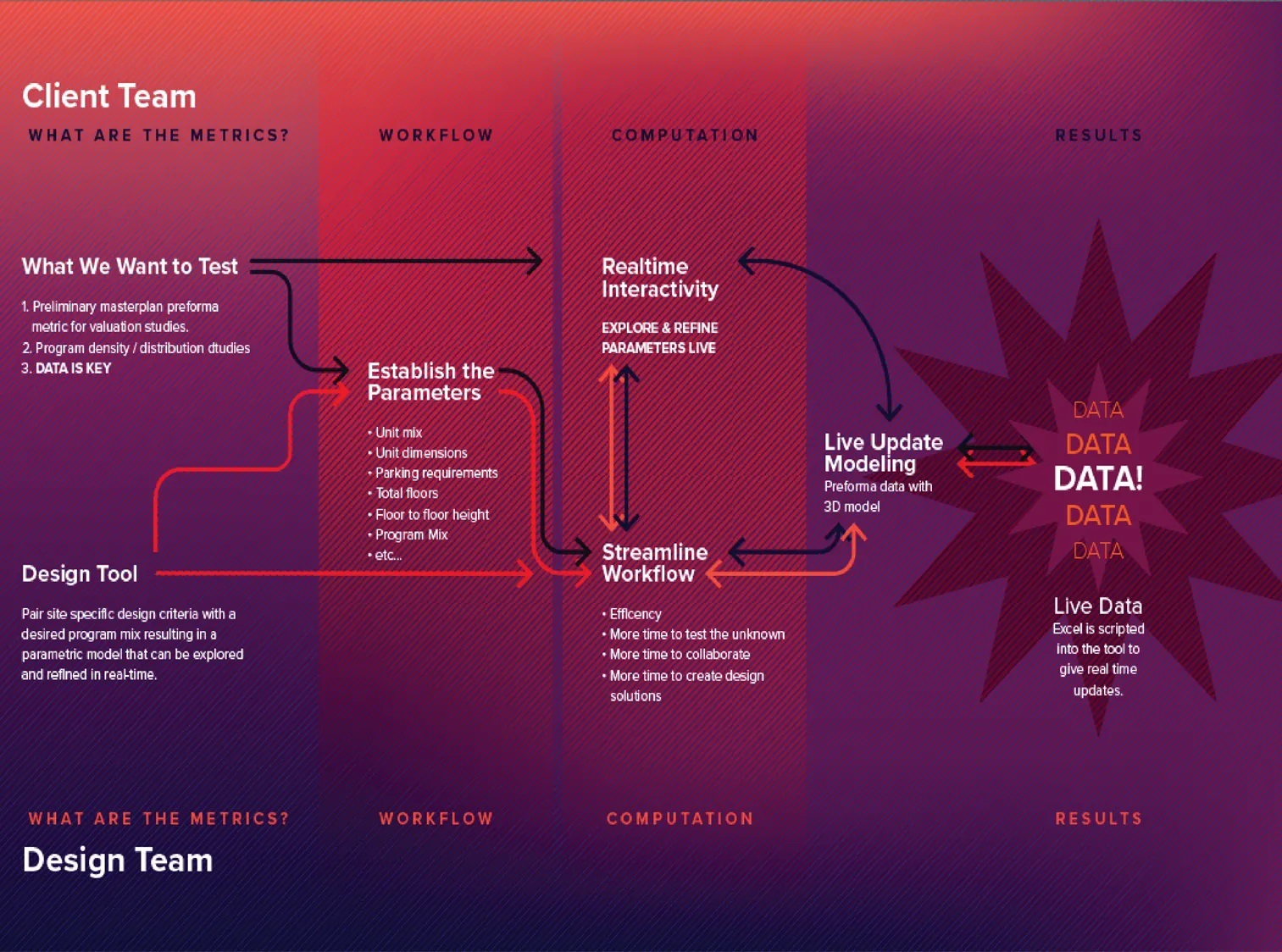

Alireza introduces Stantec’s in-house planning tool called Amp; he cites the redundancy in architectural workflows and how time-consuming production and documentation procedures leave extremely little time for actual problem-solving. Besides, the number of manual revisions it takes before finalizing a design creates many roadblocks in the design flow altogether. Amp was thus designed to enable the creation of systems defined by variables/parameters, the ranges of which create multiple variations that would otherwise be created using redundant manual workflows.

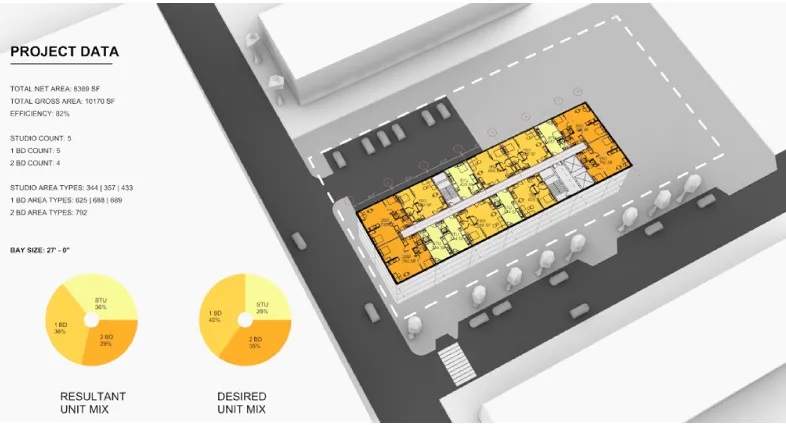

This same application lets designers create thousands of variants for each problem at hand, minimizing the time taken for feasibility studies from 3 weeks to as short as 30 minutes. Such means to handle the feasibility phase of design makes engagement with clients far more explorative and extensive. Every factor in the design that is commercially relevant to the client, like parking requirements, gross leasable floor area, unit mix, typology, etc. could be efficiently explored; besides, attributes about sustainability are also embedded in Amp, so it becomes a tool where one can visualize the consequences of design responses and make conscious design decisions driven by data.

Alireza states that the primary outcome and application of Amp was not to generate 10000 different options for the given set of constraints, but to enable an exploration of the possibilities offered by the constraints and respectively analyze them.

He offers an insight into their development of a plan repository — a plan bank, a library of flexible, customizable plans that one can select from, to directly apply for buildings, then toggle through different options to make it suit a design. This further makes engaging with clients on a design output far more effective, whilst changes could be readily made on the go.

The Amp toolkit, at the end of all the design explorations, puts out a report that enables designers to start work on the schematic design; all curves and surfaces from the design exploration in Amp could be brought in to Revit, greatly saving time and effort.

Alireza finishes, saying that the development of such tools enables non-tech savvy people to work with an equal efficacy as computational designers.

his article was authored for aec+tech, by Harish Karthick Vijay, a Design Journalist based out of Bangalore, India. Currently an undergrad student of Architecture, Harish has a high level of interest and exposure to the domain of Design Computation and Data-driven Design. Having authored multiple articles and essays for different editorials in the past, he is all set to develop a professional Design Technology career in the AEC Tech Industry.

Recent Articles

Learn about the latest architecture software, engineering automation tools, & construction technologies

Blueprints AI: Generating Construction Documentation with Artificial Intelligence

In this interview, we sat down with Al Dram, CEO and co-founder of Blueprints AI, to explore how artificial intelligence is transforming construction documentation for architects. Al shares how design teams can turn prompts, sketches, and existing files into permit-ready drawing sets—and rapidly respond to city review comments using AI-driven revisions. The conversation highlights what this shift means for architecture and AEC firms struggling with time-consuming drafting workflows and growing documentation demands.

Pioneering Technical Report Management (TRM™) for AEC Firms: A Quire Deep Dive

Learn how Quire founder Kelly Stratton is reinventing technical reporting in our latest aec+tech interview, where its purpose-built TRM™ platform, WordBank-powered standardization, AI-driven Smart Search, quality control, and the Lazarus knowledge engine come together to help AEC, environmental, and CRE teams cut reporting time and errors while unlocking their institutional expertise.

Moving to the Cloud: Egnyte’s Staged Approach for Architecture Firms

As projects grow, AEC firms are rethinking data management and collaboration. This article outlines Egnyte’s six-stage Architecture Cloud Journey—a practical roadmap for moving from on-premise systems to secure, collaborative cloud environments. From assessment to continuous improvement, it shows how to streamline workflows, strengthen security, and future-proof with AI-ready infrastructure.

SaaS Founders: Are You Timing Your GTM Right?

This article was written by Frank Schuyer, who brings firsthand experience as a founder in the software and SaaS world. In this piece, he explores how founders can unlock faster growth and stronger market traction by integrating go-to-market strategy (GTM) from the very beginning of product development—rather than treating it as an afterthought.